Click HERE to learn about

Gala Sponsorships

and Purchase Tickets

Sponsorships support our work as we celebrate our

35th Anniversary of Connecting

People ~ Wildlife ~ Community ~ Land

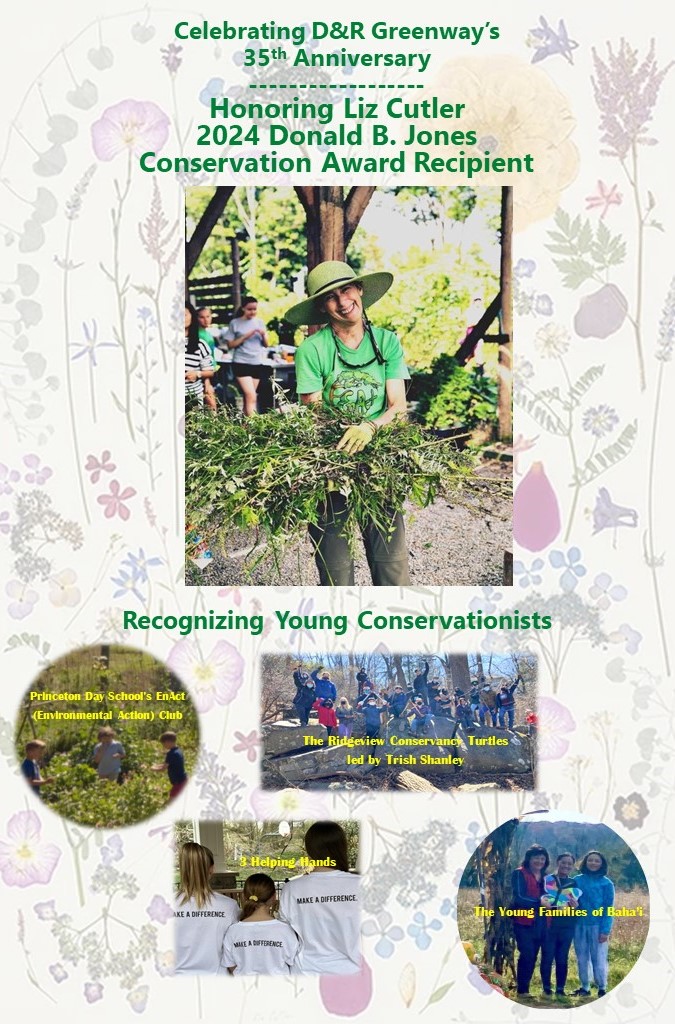

Join us on June 9th as we honor Liz Cutler and her life’s work to promote

environmental sustainability. For more than three decades, Liz has inspired

a conservation ethic in Princeton, schools across New Jersey, and beyond.

DIRECTIONS: 1 Preservation Place, Princeton (just off of Rosedale Road) next to Greenway Meadows Park

D&R Greenway’s Donald B. Jones Conservation Award is presented annually

to recognize those who have made a significant contribution to conservation.

It is a high honor that stands for personal commitment with on-the-ground results.

|

“My art is the creative manifestation of the professional work I’ve been doing my entire life, which is helping people fall in love with nature. We humans only save what we love.” — Liz Cutler, Sustainability AdvocateLiz began this remarkable journey as a teacher at Princeton Day School with a love for nature and literature. In 2005, she launched a whole school sustainability initiative alongside other stakeholders and became the Founding Director of OASIS (Organizing Action on Sustainability in Schools), a non-profit consortium of approximately 50 NJ schools working together to help each other become more sustainable. Liz continues to inspire a conservation ethic through her artwork today. Her ornate collages, made from real flowers and other objects found on quiet walks, are created through a process that preserves the natural environment. The beauty of her collages helps people slow down and appreciate their deep connection to nature. On June 9th, at the Greenway Gala, Liz’s work will be honored by

|

Click here to learn more about past recipients of the

Donald B. Jones Conservation Award

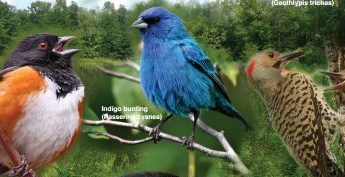

About D&R Greenway Land Trust: D&R Greenway Land Trust is an accredited nonprofit that has reached a new milestone of over 22,000 acres of land preserved throughout central New Jersey since 1989. By protecting land in perpetuity and creating public trails, it gives everyone the opportunity to enjoy the great outdoors. The land trust’s preserved farms and community gardens provide local organic food for residents of the region—including those most in need. Through strategic land conservation and stewardship, D&R Greenway combats climate change, protects birds and wildlife, and ensures clean drinking water for future generations.

D&R Greenway’s mission is centered on connecting land with people from all walks of life. Visit our Facebook and Instagram pages and www.drgreenway.org to learn about the organization’s latest news and in-person and virtual programs. D&R Greenway Land Trust, One Preservation Place, Princeton NJ 08540. The best way to reach D&R Greenway staff is by sending an e-mail to info@drgreenway.org or by calling D&R Greenway at 609-924-4646.